AULA MAGNA

FACULTAD DE LETRAS

UPV VITORIA

Los tiros veleyensis van de un lado al otro, y son contestados con otros, mientrás que seguimos esperando noticias del Juzgado de lo Penal de Vitoria. En este sentido los falsamentes acusados pasan la insoprotable pena del banquillo casi tan mal como los soldados en el libro Sin Noticias en el Frente de Erich Maria Remarque de 1929, un impactante relato de lo que es la guerra.

Recientemente, la revista HORDAGO El Salto publicó 2 entrevistas con Juan Martin Elexpuru y Alberto Barandiaran, este última con su respuesta elaborada de Idoia Filloy, y complementado con una opinión de Ignacio Rodriguez Temiño. Parrece que todo el mundo está de acuerdo sobre el horror judicial…

Pongo aquí algunos extractos que me llaman la atención. Evidentemente mi selección es subjetiva…

«Iruña-Veleia Argitu solicita que se hagan análisis de arqueometría —la especialidad relacionada con las dataciones— en tres laboratorios diferente, que se hagan excavaciones controladas en lugares contiguos y comprobar el estado de las piezas encontradas«

Por qué [Desde que se retiró al equipo de Eliseo Gil todo se ha vuelto oscuro]?

«El yacimiento estuvo un año inactivo, luego se nombró director a Julio Núñez, profesor de la UPV y autor de dos de los informes profalsedad, o sea, juez y parte. Elaboró un Plan Director para 10 años, cuya redacción costó 100.000 euros. Estuvo cinco años excavando en campañas de verano con un equipo muy reducido. Se le apartó de la docencia y del yacimiento durante seis meses por ir “en condiciones indebidas” a impartir clase según denuncias del alumnado. Luego se cogió la baja y no ha vuelto a trabajar. Nominalmente es todavía director, pero ahora mismo el yacimiento está gestionado directamente por el Museo Arqueológico de Álava. Se dejó de excavar un año y durante los tres veranos siguientes intervinieron tres equipos diferentes. No ha vuelto a publicarse nada, solamente memorias arqueológicas. En 2012 se encontró un altar con un “Veleian”, entre otras palabras.«

¿Por qué son verdaderas las inscripciones?

«No hay mente humana capaz de idear una falsificación de esta envergadura, tan variada en soportes, idiomas y temas. No hay precedentes que se le parezcan, ni remotamente. Las falsificaciones suelen referirse a una o dos piezas. Además, lo que suele ocurrir es que se trata de imitar lo conocido. Si falsificas un cuadro de Goya lo haces parecido a como pinta Goya. Si yo quisiera falsificar euskera antiguo lo haría parecer a los textos de La Rioja o de Aquitania. Y, por último, ¿a quién beneficia? A Eliseo Gil e Idoia Filloy desde luego no. Tenían un contrato en vigor. Tampoco son euskaldunes ni especialmente euskaltzales ni, por lo que sé, gente beata.«

En tu libro afirmas que “Cerdán pudo haber engañado a todos”.

«No ha presentado los análisis y, por tanto, tenemos motivos para sospechar que no los ha hecho. Tampoco sabemos si es físico nuclear. Empezó a colaborar con la Diputación de Álava con el ámbar de Peñacerrada, un yacimiento paleontológico muy mediático. Fue, incluso, ponente en el Congreso Internacional que se organizó. En 2008-2009 impartió un máster en la UPV. Si ha engañado a Lurmen, también a la Diputación y a la UPV.«

¿Estás satisfecho con el libro?

«Traté de elaborar una cronología que recogiera, más o menos, lo que pasó, y también quise que hubiera muchas voces. Sobre todo, las de los arqueólogos que trabajaron en el yacimiento y la de Mertxe Urteaga, la directora del Museo Oiasso de Irun, el gran yacimiento vasco de época romana. Ahora me da pena no haber entrevistado a Idoia Filloy, la subdirectora del yacimiento de Iruña-Veleia. En su momento pensé que su papel había sido más secundario, pero con el tiempo he llegado a la conclusión de lo contrario. Visto con perspectiva, la verdad es que hubo bastante gente que habló específicamente, y por primera vez, para el libro.»

¿Y la acogida del público?

«No fue un best seller. Se lo desprestigió mucho, pero nadie ha refutado lo que se cuenta en él. La editorial comentó al principio la posibilidad de hacer una traducción al castellano, pero luego se descartó. También sé que el libro hizo daño a alguna gente.»

¿A qué gente?

«A la que no quería saber, sino creer.«

Se defiende que existen ejemplos similares en otros yacimientos…

«Hay que recorrer todo el Mediterráneo para encontrar casos equivalentes de algunos de los nombres propios, las emes (M), las comas, las grafías, las flechas, los motivos religiosos o los dibujos que aparecen en Iruña-Veleia. Dicho de otro modo: dado que no existe ningún otro caso en toda Europa con tal cantidad de restos excepcionales, no es científicamente razonable.»

¿Y cuál sería la segunda razón?

«No se puede tirar adelante cuando 26 expertos de primer nivel defienden la falsedad o la imposibilidad de la verificación. La comisión que llevó a cabo el análisis científico fue escogida, de mutuo acuerdo, por la Diputación de Álava y por el propio Eliseo Gil, el director de las excavaciones.»

¿Y sobre la judicialización del proceso?

«Si lo que se quiere demostrar es que Eliseo Gil, Rubén Cerdán y Óscar Escribano —arqueólogo, supuesto físico nuclear y geólogo respectivamente— falsificaron las piezas, eso solo se podrá acreditar si hay un testigo que lo ratifica o si ellos mismos lo aceptan. No tiene pinta de que eso vaya a ocurrir. En todo caso, que ocho años después tres personas a las que se les acusa de los delitos de estafa y de daños contra el patrimonio público sigan pendientes de juicio es profundamente injusto. Y que se enfrenten a peticiones de siete años de cárcel es una barbaridad que yo también quiero denunciar. Eso ni es justicia ni es nada. Si a estas alturas no se han encontrado pruebas, que se archive el caso.«

«¿No hay ninguna prueba que respalde la acusación?

«Se ha transmitido a la opinión pública un error de concepto: no va a poderse demostrar la veracidad o la falsedad porque ese es un asunto científico, no jurídico. De todas maneras, hay un estudio grafológico encargado por la Diputación Foral de Álava, que sostiene que el autor de las falsificaciones es Eliseo Gil, con un alto grado de probabilidad. Creo que esa podría ser la única prueba.»

«No hay nada en el contenido de los grafitos que sea imposible en la época en la que el método arqueológico ha permitido situarlos. De hecho, a lo largo de estos años hemos podido encontrar paralelos de época romana de prácticamente todos aquellos aspectos que se consideraban como “imposibles” en los informes de la comisión. Algunos ciertamente conocidos sólo por unos pocos especialistas en el mundo. El hecho de que según algunos aúnen demasiadas “rarezas” no es sino evidencia de lo poco que sabemos de la Antigüedad.

Los informes de la famosa “comisión de expertos” no aportaron ni una sola prueba de falsificación, ni una, ni siquiera los de corte propiamente “científico”. Antes bien se fundamentan en una serie de argumentos de autoridad que en muchos casos, quedan contradichos por la propia documentación de época romana, tal y como hemos podido demostrar. Esto nos llevaría a planteamientos graves sobre el nivel de especialización de algunos miembros de dicha comisión, e incluso sobre la posible servidumbre a intereses particulares de diverso tipo que el paso de los años ha demostrado en algunos casos. Y esto es aún peor que lo anterior.

El hecho de que un material arqueológico sea novedoso o único (que no les engañen, no hay ningún rólex -ejemplo con el que un catedrático intentó banalizar el hallazgo- ni nada que sea imposible en época romana) no es en absoluto evidencia ni prueba de imposibilidad y, menos aún, de falsedad. Lo que pasa es que al parecer algunos investigadores que se dedican a reconstruir el pasado no llegan a ser conscientes de que sólo se nos han conservado algunas evidencias del mismo y que no todas han sido encontradas. De vez en cuando tiene lugar un hallazgo singular que no es sino evidencia de algo que fue más generalizado y que desbarata aquello que creíamos. Así que siempre hay que distinguir entre hipótesis históricas y pasado y tener en cuenta que la aparición de nuevas evidencias del pasado puede llevar al traste con algunas teorías establecidas. Y pienso que eso es parte de lo que ha ocurrido con los “hallazgos excepcionales” de Iruña-Veleia, que alguno de los contenidos de los grafitos demostrarían que determinadas propuestas históricas y lingüísticas en boga en los ámbitos académicos no se sostienen. Y ello explicaría cómo algunos reaccionaron rápidamente contra ellos al ver amenazados sus postulados teóricos por datos venidos directamente del pasado y conservados en estratos arqueológicos. No tengo ya muchas dudas de que la aparición de textos y palabras escritos en lengua vasca, con la obvia lectura política que algunos pudieran hacer y han hecho ya, subyace también desde el principio en el intento de desacreditar el hallazgo. Pero, qué le vamos a hacer, es lo que hay.

Barandiaran afirma que “no se puede tirar adelante cuando 26 expertos de primer nivel defienden la falsedad o la imposibilidad de la verificación”. Vamos a aclarar esta cuestión e invito a comprobar lo que voy a decir (en www.sos-irunaveleia.org o en la web de la DFA). Nunca hubo 26 expertos de la comisión (que por cierto, no fueron elegidos de común acuerdo entre la DFA y Eliseo Gil, sino que a éste no le quedó otra que aceptar la composición de la misma que fue decidida unilateralmente por la institución foral, lo sé de primera mano), nunca elaboraron unas conclusiones consensuadas, ni se pronunciaron de forma unánime con respecto a la falsedad del hallazgo. Ni uno solo de los informes presenta prueba alguna de falsedad sino que contienen fundamentalmente argumentos de autoridad muchos de ellos rebatibles con la propia documentación de época romana. En mi opinión la Comisión no investigó los grafitos, se limitó a realizar una serie de informes para sustentar una decisión institucional ya tomada de antemano de declarar falsos los grafitos y de expulsarnos del yacimiento. Era una comisión formada únicamente por miembros de la UPV, con algunos asesores externos, en la que faltaban especialistas de alto nivel para evaluar algunas de las principales temáticas presentes en los grafitos, algunos de sus miembros ya se habían pronunciado públicamente en contra del hallazgo antes de analizarlo (concretamente Lakarra y Gorrochategui que, en contra de lo que señala Barandiaran, sí verían peligrar sus postulados teóricos) y otros tenían intereses en la gestión del yacimiento tal y como se terminó demostrando. Así que no sólo podíamos tirar adelante con la defensa de la autenticidad de los grafitos a pesar de los informes de la comisión, sino que creo que ésta tendrá que responder tarde o temprano por su cuestionable papel en este caso. De todas maneras, pienso que el futuro dejará a cada cual en el lugar que le corresponde en esta historia.

Barandiaran plantea un escenario para contextualizar el supuesto “crimen” que no hay por dónde cogerlo, simplemente porque no es cierto nada de lo que dice. Y lo puedo afirmar con rotundidad porque yo estaba allí y porque puedo demostrarlo. Él no. Y creo que el público tiene derecho a saber que ciertas cosas que se dicen simplemente no son verdad. Veamos. Nosotros comenzamos a trabajar en el yacimiento de Iruña-Veleia en el año 1994 como colofón a un proyecto de investigación sobre el mundo prerromano y romano en Álava que estábamos desarrollando. Comenzamos como se hacían antes las cosas, con subvenciones, con mucho trabajo altruista y animados por una inmensa vocación personal. Hacia el año 2000-2001 y tras una serie de vicisitudes, comenzamos una nueva etapa gracias a la firma de un convenio con Eusko Tren que iba a permitir desarrollar un proyecto de investigación de envergadura en el yacimiento y profesionalizar el trabajo del equipo. El proyecto tuvo un desarrollo normal en el plano científico, se iban encontrando muchos datos, estructuras y materiales muy interesantes, algunos bastante espectaculares. Y es que Iruña-Veleia es un yacimiento bastante rico en hallazgos y bien conservado, en el que continuamente se iban obteniendo resultados. No es cierta la afirmación de Barandiaran de que “el equipo sufría presiones y amenazas por parte de Euskotren con retirar el mecenazgo si no aparecía algo de calado”. Insisto, esto es rotundamente falso. El mecenazgo estaba blindado por un Convenio que no se podía romper unilateralmente sin una buena razón y en dicho Convenio no se condicionaba su continuidad a la aparición de hallazgo alguno. Además y como ya he dicho, Iruña-Veleia es un yacimiento rico en hallazgos que se iban dando continuamente desde el principio. No hacía falta la aparición de “grafitos excepcionales” para la continuidad del proyecto, como pretende engañosamente sugerir Barandiaran, que ya estaba garantizada hasta el 2010-2011 antes de su aparición. Recuerdo que basa su “información” en un informante anónimo, gran fuente.

Tampoco es cierto que “la empresa ferroviaria colocara a un director de comunicación a sueldo de la entidad” en nuestro equipo desde el principio. No sé a qué quiere llegar con eso, supongo que pretende sugerir un dirigismo de Eusko Tren que no existió. Sí lo tuvimos, pero años después, a decisión nuestra y para liberar al equipo de un tipo de trabajo que no era propiamente el científico en el que había que centrarse.

Tampoco es cierto lo que dice respecto a Henrike Knörr y José Luis Álvarez Enparantza “Txillardegi”, sobre los que afirma “diría que tuvieron dudas desde el principio”. Que quede claro, eso lo dice Barandiaran y es él quien lo supone en boca de los otros. Opino que es indigno que haga esto con quienes ya han muerto. Nunca dijeron tal cosa. Puedo afirmar porque fui testigo presencial de ello que “al principio” la reacción de Knörr fue de sincera emoción cuando le enseñamos los grafitos en euskera, mostrando su convicción de que eran auténticos al provenir de una contexto arqueológico. Y lo dijo públicamente. Sólo presiones posteriores que nos constan, le hicieron matizar su opinión por la que terminó situando sus hallazgos en torno al siglo VII en un mail que mandó, ya casi al final de su vida, a Lakarra. El indigno y manipulado uso que esta persona hizo del mismo creo que ha quedado sobradamente demostrando, ya que cortó el texto en un punto concreto cambiando su sentido, para hacer creer que Knörr al final había apoyado la tesis de la falsedad. Y eso sólo se supo cuando la familia hizo público el mail completo. Y ahora Barandiaran pretende algo similar. Me pregunto cómo tiene la osadía de decir que como Knörr terminó diciendo que los grafitos en euskera tenían que estar en torno al VII y la Arqueología los sitúa en el III (cosa que no es tampoco cierta porque los hay de varias épocas) son falsos. Tampoco es verdad lo que dice de Txillardegi y se puede demostrar con las cartas manuscritas que envió a Juan Martin Elexpuru antes de morir y en las que dice claramente que cree que los grafitos en euskera son auténticos. En fin, sin palabras.

Otra aclaración: Edward C. Harris, creador del método de registro estratigráfico que lleva su nombre y que es el más utilizado en la Arqueología actual, no sólo avaló el trabajo arqueológico de Lurmen sino que también dio su opinión sobre la manera en que se ha gestionado la problemática y sobre los grafitos de la siguiente manera “Uno no necesita ser arqueólogo para aceptar que estos objetos arqueológicos son auténticos, ya que los argumentos para declararlos falsos desafían toda lógica y entendimiento de las circunstancias en las que los falsificadores normales actúan, por no hablar de la total ausencia de beneficio económico o de otra índole que supuestamente debería reportar a los arqueólogos que presuntamente crearon estas 400 “piezas maestras” de grafitos antiguos”.

La postura de Barandiaran con respecto a los grafitos siempre ha estado clara, él sabrá a qué responde. Pero lo que no está bien es mentir o inventar. Tampoco es un buen recurso periodístico recurrir a informantes que no quieren dar la cara o que puedan tener intereses poco dignos. Ya ha habido demasiados de esos en toda esta historia. Su libro Veleia afera que pretende ser un referente del caso es claro indicativo de dicha postura. Es un referente, sí, pero únicamente de la “versión oficial” como cualquiera que lo lea podrá comprobar. Afirma que pretendía elaborar una cronología de lo que pasó con muchas voces contando la historia. Lo que pasa es que lo hizo dando voz y cediendo el protagonismo narrativo exclusivamente a algunos arqueólogos, epigrafistas, historiadores, políticos e incluso algún amateur que defendían la falsedad de los grafitos, algunos de los cuales no eran en absoluto testigos de lo que ocurrió y algunos otros que ya habían manifestado su animadversión al equipo de Lurmen. En total entrevistó para el libro a 13 personas alineadas con la idea de la falsedad (concretamente y espero no dejarme a nadie serían Julio Núñez, Miguel Ángel Berjón, Jose Ángel Apellániz, Agustín Azkárate, Mercedes Urteaga, Alicia Canto, Juan Santos, Pilar Ciprés, Isabel Velázquez, Lorena López de Lacalle, Miren Azkárate, Agustín Otsoa Eribeko y Salvador Cuesta “Sotero”).

No contrastó ninguna de sus opiniones y afirmaciones, las dio como buenas sin más. No entrevistó a testigos de la otra parte, ni a nadie de los que pensamos que el hallazgo es auténtico o de los que pedimos una resolución analítica del asunto. Sí introdujo algunas voces, concretamente 3, las de Eliseo Gil, Juan Martin Elexpuru y Hector Iglesias pero recurriendo a entrevistas hechas bastante tiempo atrás para Berria, supongo que pretendiendo un barniz de ecuanimidad que es obvio que no existe. Por tanto incluye un montón de testimonios sin contrastar que, en mi opinión, distan mucho de ofrecer una visión objetiva y neutral del hallazgo, antes bien, se muestra un panorama totalmente sesgado que se reconoce claramente. Aunque sí que es cierto que mencionan los foros y blogs que en aquellos días funcionaban tanto de un sentido como en el otro, ningunea totalmente el libro que ya había sido publicado por Juan Martín Elexpuru “Iruña-Veleiako Euskarazko Grafitoak” del 2009, así como la web www.sos-irunaveleia.org, donde se ofrecía información científica del hallazgo y se iban colgando informes en todos los sentidos sobre el tema. Tampoco menciona el desastre realizado con una excavadora y dos camiones por el nuevo director Julio Nuñez cuatro meses antes de la publicación de su libro. Así que si a algo hizo daño éste no fue a los que según él “quieren creer”, sino a la verdad. Curioso que los que “quieren creer” son los que han estado peleando denodadamente por una investigación científica de carácter analítico para la resolución del tema.

Finalmente, quería mencionar una cuestión y es la relativa a la supuesta prueba contra Eliseo Gil como supuesto autor de las falsificaciones, consistente en un estudio grafológico aportado por la Diputación Foral de Álava al proceso y generosamente pagado con 36.000 euros del erario público. El mismo Alberto Barandiaran elaboró un artículo el 30/01/2010 para Berria donde, a nuestro juicio, fue más allá de su cometido de informar, exponiendo una serie de elucubraciones indemostrables para poner el dedo acusador contra Eliseo Gil, cuando éste aún ni había tenido acceso al estudio por lo que no tuvo oportunidad alguna de defenderse. En cualquier caso, he de aclarar que el Juzgado de instrucción solicitó a la sección de Documentoscopia y Grafística de la Unidad de Policía Científica de la Ertzaintza, un informe pericial para el cotejo de los grafitos y las inscripciones de la letrina (comparativa en la que se basa dicho estudio grafológico). Pues bien, la jefa de dicha sección emitió un escrito en el que comunicaba “la imposibilidad de la realización del estudio solicitado” exponiendo las razones de ello y desacreditando la fiabilidad y la base científica de una pericial de ese tipo. Este informe desmontaría totalmente la supuesta prueba grafológica presentada por la diputación contra Gil. Sin embargo, Barandiaran la sigue ventilando como tal.

Terminaré diciendo que no debemos olvidar que los “hallazgos excepcionales” de Iruña-Veleia son, en primera instancia, un material arqueológico contextualizado estratigráficamente. Nada en su contenido es imposible en el momento cronológico en el que el método arqueológico ha permitido situarlos. No hay una sola prueba de que hayan sido falsificados. Son excepcionales porque aportan contenidos y grafismos novedosos producidos en un contexto doméstico. Como patrimonio cultural de todos, merecen una resolución científica que dirima objetivamente sobre su autenticidad o falsedad. Y así, liberados de las dudas, ocuparán nuevamente el lugar que les corresponde como un valioso testimonio del pasado conservado a través de los siglos, para aportarnos esa información que los propios habitantes de la antigua Veleia romana dejaron grabada para la posteridad, aún sin pretenderlo.«

«Los casos de falsificaciones de objetos arqueológicos suelen contar con dos facciones, una que avala la autenticidad y otra que la cuestiona. Normalmente, terminan su ciclo vital cuando el engaño queda acreditado y el mundo académico lo admite. En el caso de los “hallazgos extraordinarios” de Iruña-Veleia, además, su tosquedad ha provocado hilaridad en círculos especializados en epigrafía latina (imagino que para bochorno de quienes lo avalaban dentro de la propia UPV/EHU), con lo que podría decirse que la refutación de su originalidad no ha exigido de debates complejos.

Sin embargo, los partidarios de la autenticidad (o “veristas” en el argot usado en internet y en los medios de comunicación) han querido zafarse acudiendo a la libertad incontrolada de la red que, en este caso, ha mostrado su doble cara. Al inicio, fue el medio en el que comenzó a cuestionarse la autenticidad de los hallazgos que venían presentándose. Al final, ha servido como refugio de un negacionismo cerril, y se ha convertido en la trinchera de la facción “verista” para defender su inocencia enhebrando un discurso victimista con pocas aristas académicas. Una especie de mesa de camilla virtual en la que se sientan apenas cinco personas que perseveran en los mismos tópicos. Pero ahí siguen. Lo lógico hubiese sido dar la batalla en revistas académicas, defendiendo la autenticidad de las óstraka pero nada de eso se ha hecho ni es previsible que se haga.

En ese sentido, se les acusa también de un delito de daños al patrimonio arqueológico por haber manipulado unos fragmentos de cerámica originales para grabar las inscripciones. Existe poco margen para considerar esa acción como delictiva, habida cuenta la irrelevancia que tienen para el patrimonio arqueológico vasco unos fragmentos de cerámica y unos trozos de hueso similares a los miles que están desatendidos en yacimientos y fondos museísticos. Por ello, resulta todavía más extraña, si cabe, la desorbitante valoración llevada a cabo en la prueba pericial (600€ por pieza) por parte de la Diputación Foral.

Resulta desconcertante admitir que exista el deseo de castigar de la manera más contundente posible. Esta sobreactuación quizás se explica mejor si se considera que el núcleo de la falsificación apuntaba al corazón de un sector importante del nacionalismo político vasco: euskera y cristianismo tempranos. El engaño habría cabalgado sobre unos sentimientos abertzales que primero operaron para proclamar con júbilo los hallazgos y que, después, sobreactuaron cuando se vieron objeto del burdo engaño.«

«Esta sobreactuación quizás se explica mejor si se considera que el núcleo de la falsificación apuntaba al corazón de un sector importante del nacionalismo político vasco: euskera y cristianismo tempranos. El engaño habría cabalgado sobre unos sentimientos abertzales que primero operaron para proclamar con júbilo los hallazgos y que, después, sobreactuaron cuando se vieron objeto del burdo engaño.»

Copio parte del artículo sobre el profesor Javier de Hoz de la página Hespería, Banco de Datos de Lenguas Paleohispánicas, relacionado con la muerte de su fundador.

|

| https://www.ucm.es/dialectos-griegos/javier-de-hoz-bravo |

«La familia paleohispánica se encuentra de luto por el fallecimiento de Javier de Hoz (1940-2019)

La familia paleohispánica se encuentra de luto. Javier de Hoz, nuestro maestro, compañero y amigo, acaba de fallecer en Madrid a los 78 años de edad, dejándonos a todos sumidos en una profunda tristeza y un desconsolador sentimiento de orfandad. Hace escasamente siete semanas lo habíamos tenido con nosotros en Vitoria, algo doliente por su enfermedad, pero lúcido como siempre y especialmente contento por encontrarse rodeado de los miembros de esta pequeña familia paleohispánica que él directa o indirectamente ha logrado crear en los últimos cuarenta años. Pudimos comprobar su satisfacción al ver que por fin se iban tomando decisiones para la celebración del próximo Coloquio de la disciplina en Loulé (Portugal) y su inquebrantable ánimo por continuar con sus investigaciones sobre la epigrafía meridional y del suroeste peninsular a fin de culminar la parte correspondiente del Banco de Datos Hesperia.Javier de Hoz (Madrid 1940) fue catedrático de Filología Griega, primero en Sevilla (1967?), luego en Salamanca (1969) y finalmente en la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (1990), de la que pasó a ser profesor emérito en 2010. Como filólogo griego se interesó por la literatura, especialmente por la literatura arcaica griega y por el teatro, en cuyo análisis aplicó de manera novedosa los principios del estructuralismo. Pero no era un hombre de horizontes limitados, de modo que sus ámbitos de interés alcanzaron campos muy extensos, como la epigrafía de muchas lenguas antiguas (ya que para él la epigrafía no quedaba reducida, como para muchos profesores titulados de esta materia, a «epigrafía latina»), la numismática, la edición filológica de textos, la lingüística histórica, la arqueología y demás ciencias auxiliares de la historia o la filología. Todas estas disciplinas, abordadas con un espíritu integrador heredero de la noción wilamovitzana de Altertumswissenschaft, las utilizó con un arte y naturalidad incomparables en el estudio de las antigüedades hispanas, es decir, en el campo de la paleohispanística.Aunque sus primeros trabajos de investigación fueron dedicados mayoritariamente a cuestiones de literatura griega –ámbito en el que dirigió la tesis de muchos discípulos en Salamanca–, desde muy pronto sintió interés por las lenguas, la epigrafía y la cultura de las lenguas prerromanas de Hispania. Ahí están sus primeros trabajos sobre hidronimia antigua europea, en la estela de Krahe, o sobre ciertos grafitos de Huelva, que le llevaron a entablar muy pronto una relación con J. Untermann. Su destino en Salamanca fue crucial para impulsar esta parte de su actividad investigadora, ya que allí se encontró con la presencia de Luis Michelena, un hombre de una enorme solidez científica como lingüista histórico y como especialista en lenguas prerromanas, tanto indoeuropeas como no indoeuropeas. Y en esa compañía sobrevino el hallazgo del gran Bronce de Botorrita, que revolucionó el panorama de los estudios paleohispánicos y de los célticos en particular, un tanto estancado desde la síntesis de Tovar de los inicios de los 60. En compañía de Michelena dedicó el primer estudio monográfico al bronce (1974), iniciando una trayectoria que lo conduciría en pocos años a convertirse en una referencia inexcusable en nuestros estudios. Ese mismo año se celebró en Salamanca el primer Coloquio de Lenguas y Culturas prerromanas de la Península Ibérica (denominadas paleohispánicas desde el III Coloquio en Lisboa) que se han venido celebrando sin interrupción cada cuatro años aproximadamente. En estos momentos Javier de Hoz ocupaba por méritos propios la presidencia del Comité Internacional de los Coloquios, después de Antonio Tovar y de Jürgen Untermann.Al igual que los grandes maestros recién mencionados, Javier de Hoz tenía una concepción unitaria de la disciplina, cuya razón de ser estriba, por un lado, en que toda la epigrafía prerromana peninsular está redactada en una escritura (o en una familia muy estrecha de escrituras) que fue utilizada por lenguas de origen y filiación diferentes, y por otro, en que la mayoría de los textos indígenas, ya sean ibéricos o celtibéricos, son el resultado de la aculturación ejercida por las culturas y epigrafías clásicas griega o latina. Dedicó múltiples trabajos a cuestiones de escritura, especialmente a las fases más antiguas de la adopción en el horizonte tartésico y su evolución interna posterior, a las relaciones entre los diferentes sistemas, a la expansión de la escritura y presumiblemente de la propia lengua ibérica, que ideó como una expansión vehicular muy relacionada con su uso como lengua de comercio, combinando con maestría y elegancia análisis formales y nociones sociolingüísticas para ofrecer un sugerente panorama de la variedad y la unidad epigráfica y lingüística.Se preocupó por cuestiones de lingüística, más de corte tipológico y formal en el caso ibérico, como es normal, y más de detalle en cuestiones de fonología o de morfología celtibérica, sin perder nunca de vista las coordenadas arqueológicas y el contexto cultural al que pertenecía cada uno de los textos que analizaba. Nunca jamás el lector tendrá la sensación de que Javier de Hoz está hablando de oídas o utilizando información de segunda mano, dado su amplísimo dominio filológico de la documentación. Y teniendo como puntos de anclaje su formación griega y su investigación paleohispánica hizo aportaciones notables también en campos relacionados con las lenguas del Mediterráneo, como el fenicio, el galo y algunas lenguas de Italia.Siempre estuvo al tanto de los avances y las novedades científicas que se producían en la disciplina. En Salamanca era, sin duda, uno de los profesores más implicados en la compra de bibliografía internacional y en la renovación de los fondos bibliográficos del, por otro lado, excelentemente dotado Seminario de Clásicas. Consideraba imprescindibles las relaciones con centros de investigación prestigiosos del extranjero, de modo que desde joven visitó universidades alemanas, aprovechándose de una ayuda de la Fundación A. v. Humboldt, y realizó varias estancias largas en la Universidad de Cambridge (Mss.). Su perspicacia y voluntad por situarse a la vanguardia de la innovación le llevaron a la convicción de que una edición actualizada y renovada de las inscripciones paleohispánicas no era posible en los momentos actuales sin recurrir decididamente a los medios digitales de recopilación, análisis y difusión de la información. Así ideó la creación del Banco de Datos Hesperia sobre Lenguas y Epigrafías Paleohispánicas ya en los años 90, que se ha convertido desde su apertura al público en 2014 en un instrumento pionero para el estudio de dichas inscripciones y en modelo para otros proyectos similares sobre epigrafías y lenguas antiguas.Al final de su carrera académica nos regaló a todos con una obra que solamente él podía realizar: una recopilación sistemática y ordenada de toda la documentación histórica, epigráfica y lingüística referente a las lenguas paleohispánicas, comentada y analizada desde las investigaciones más avanzadas y actualizadas. Me refiero a la Historia Lingüística de la Península Ibérica en la Antigüedad, cuyos dos primeros tomos salieron en 2010 y 2011 respectivamente, editados por el Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (Madrid), y cuyo tercer volumen, dedicado al mundo indoeuropeo peninsular, tenía prácticamente terminado.Hemos perdido no solo a un profesor empeñado en la dignidad de la docencia y a un investigador de amplios horizontes, extremadamente bien informado y dotado de un saludable sentido común, sino también a un hombre de un trato exquisitamente respetuoso con sus colegas –sobre los cuales jamás salió de su boca ningún comentario despreciativo– , en definitiva, a un aristócrata de espíritu, que concibió la vida como un ejercicio para la mejora personal a través del cultivo de las humanidades y de las personas que mejor las encarnaban.Nuestro más sentido pésame a su desconsolada esposa, Mª Paz García-Bellido, su inseparable compañera en la vida y en los estudios, y a sus afligidos hijos.

Su recuerdo permanecerá para siempre en nuestros corazones.»

Fuente: http://blogak.goiena.eus/elexpuru/

Precio: 9,90 €

Mucha gente se hace la pregunta: ¿Pero qué está pasando con Iruña-Veleia? Han pasado más de 12 años desde que se produjeran los “hallazgos excepcionales” y todavía no sabemos si son verdaderos o falsos. Lo que sabemos es que los supuestos falsificadores siguen bajo la espada de Damocles en espera de un juicio que no llega, con peticiones de muchos años de cárcel.

En este libro el autor trata de responder a la pregunta, haciendo primeramente una crónica detallada de los acontecimientos, sin dejar de lado ninguna de las cuestiones que afectan a la polémica: intereses de la universidad vasca, la decisiva actuación de algunos filólogos que ven cuestionadas algunas teorías sobre el euskera antiguo, el asunto de la euskaldunización tardía, la posible intervención del Vaticano, el caso Cerdán, la ingenuidad e ignorancia de los políticos vascos, etc.

La descripción e interpretación de los hallazgos ocupa también un lugar central, así como los argumentos a favor y en contra de la autenticidad. Y por supuesto el asunto de las analíticas y las dataciones, pues existe unanimidad en que un laboratorio especializado en Arqueometría podría dirimir la cuestión en muy poco tiempo. Se indaga en los fuertes y oscuros intereses que impiden la resolución del caso.

Se incide también en la Importancia de los hallazgos de Iruña-Veleia : historia y filología de la lengua vasca, paso del latín al romance, expansión de la religión cristiana, etc. Un yacimiento espectacular oscurecido por negros nubarrones, un sitio con un enorme futuro pero prácticamente abandonado.

En definitiva, un libro que pretende remover conciencias y acelerar el esclarecimiento del caso proporcionando información y documentación de primera mano, mucha de ella inédita.

Prezioa: 9,90.

Jende askok bere buruari egiten dion galdera: baina zer ari da gertatzen Iruña-Veleian? Hamabi urte igaro dira “ezohiko aurkikuntzak” egin zirela eta oraindik ez dakigu benetakoak ala faltsuak diren. Badakiguna da balizko iruzurgileak Damoklesen ezpatapean jarraitzen dutela sekula heltzen ez den epaiketaren zain, eta urte askoko kartzela-zigorra eskatzen zaiela.

Liburu honetan galderari erantzuten saiatzen da egilea, lehenik gertakizunen kronika zehatza eginez, eztabaidarekin zerikusia duen ezer alde batera utzi gabe: euskal unibertsitatearen interesak, filologo batzuen jokaera erabakigarria antzinako euskarari buruzko zenbait teoria zalantzan jartzen delako, euskalduntze berantiarraren auzia, Vatikanoaren ustezko parte-hartzea, Cerdán kasua, euskal politikoen sineskortasuna eta ezjakintasuna, etab.

Aurkikuntzen deskripzioak eta interpretazioak ere leku handia hartzen du, benetakotasunaren aldeko eta aurkako argudioek bezalaxe. Eta jakina, analitiken eta datazioen gaiak; izan ere, zerbaitetan adostasuna badago, honetan da: Arkeometrian berezitutako laborategi batek oso denbora gutxian erabakiko lukeela auzia.

Iruña-Veleiako aurkikuntzen garrantziaz ere hitz egiten da: euskararen historia eta filologia, latinetik erromantzerako pausoak, erlijio kristauaren zabalkundea, etab. Aztarnategi ikusgarria da, laino beltzek ilundua dutena; etorkizun oparoko lekua, erdi abandonatua dagoena.

Azken batean, kontzientziak astindu eta auziaren argitzea bizkortu nahi duen liburua da, lehen eskuko informazioa eta dokumentazioa eskainiz, horietako asko argitara gabea.

|

| Presentación del libro en Donostia, el 14 de enero 2019. |

El 19 de noviembre 2008 una Comisión Científica Asesora con únicamente miembros académicos de la Universidad Vasca declaró todas las piezas con inscripciones de Veleia (en términos judiciales 476 piezas) falsas, y esto por unanimidad científica.

Con el tiempo hemos aprendido mucho sobre dicha Comisión. Fue formada y presidida por la política Lorena Lopéz de Lacalle entonces Diputada de Cultura, alguien con ninguna formación científica, el Secretario de la Comisión… pues su director de Patrimonio. El mismo que no fue mucho al yacimiento para verificar si todo iba bien allí con la arqueología, aunque fue responsable final. Curiosamente será su subordinada Amalia Baldeón que perderá su puesto como directora del Museo de Arqueología.

Pero lo más curioso es que este Secretario se dedicó a escribir conclusiones secretas, que nunca han sido hechas públicas por la DFA… y nunca han sido ratificadas por los otros miembros de la Comisión donde se afirma que:

«4. Elaborar un nuevo proyecto arqueológico para Iruña-Veleia, con la participación de la comunidad científica y en concreto de la Universidad del País Vasco. Los fines de este nuevo proyecto serán la salvaguarda, promoción, potenciación de imagen, excavación, consolidación, expropiación, investigación, musealización, puesta en valor y difusión del Patrimonio Arqueológico de Iruña-Veleia, proporcionándole todas las infraestructuras necesarias.» http://www.sos-irunaveleia.org/conclusiones

|

| En varios surcos de letras de la pieza 13371 aparecen aparentemente cristales de carbonato, lo que indica su antigüedad |

Y quitar a LURMEN para poner a la Universidad cuyos miembros formaron la Comisión, con más en concreto el Prof. Nuñez como miembro de dicha Comisión como nuevo Director del yacimiento de Iruña Veleia, no va en contra del principio de la neutralidad, de que uno no se puede ser juez y beneficiado?

Espera un momento… por qué la Comisión se llama ‘Asesora’. Como la ex-Diputada explicó el 15 de febrero 2008 en Juntas Generales, esto es para asesorar a la Diputación sobre los hallazgos excepcionales. ¿No es de locos que la Presidenta y el Secretario de una Comisión quien debe asesorar son al mismo tiempo los responsables que buscan asesoramiento?

Hay uniformidad científica… pero en el informe Químico no leemos que las inscripciones son falsas, sino unas frases muy pocas inteligibles sobre continuidad de pátina no en la mayoría de los casos pero en una minoría sí…

No es de sorprender que posteriormente aprendemos que el Prof. Madariaga no había terminado su investigación y ni en principio de enero 2009, unas 7 semanas más tarde, había terminado (según sus declaraciones delante la Ertzaintza nunca las terminó).

No es absolutamente raro que una Diputada-Presidenta no espere el fin de lo que es quizás la investigación más importante, la de la demostración física de la falsificación?

Delante estas gravísimas infracciones contra la objetividad científica hay un detalle que el día de la declaración de la falsedad no se disponía de los informes definitivos sino de unos resúmenes en muchas ocasiones. Lo lógica sería – si hablamos de una Comisión – que sus miembros tuvieron el tiempo de estudiar los otros informes y llegasen a unas conclusiones consensuadas y reflexionadas.

Pero no… la Presidenta tuvo unas prisas terribles para nombrar a Nuñez, y los obstáculos que ella encontraba en su camino iba eliminando con su excavadora (en este sentido muy parecido a Nuñez en su gestión de Veleia). Eliseo Gil, el ex-director no se dejó intimidar, y poco a poco aportó argumentos que dejaron los informes de la Comisión cada vez más en el rincón de las dudas (con una ingente cantidad de errores factuales). Una veintena de informes desde diversos especialidades defienden la autenticidad o necesecitadad de más investigación.

En marzo 2009, en el momento que la ex-Diputada inició formalmente sus negociaciones con la Universidad Vasca para nombrar a Nuñez (oficialmente únicamente como redactor de una Plan Director), se interpone una querella contra entre otros Eliseo Gil, por falsificar las piezas y falsificar unos informes firmados por Rubén Cerdán, una figura presentada por la Diputación misma a los arqueólogos de Álava.

Criminalizar a Eliseo Gil, mientras graves dudas sobre la falsedad siguen existiendo, es estratégicamente un movimiento genial. ¿Qué científico quiere defender a algo excavado por unos criminales?

Después de 9 años y medio de querella ningún reconocido experto en arqueometría ha estudiado las inscripciones, no existen pruebas fehacientes de su falsedad, ni se ha demostrado de ninguna manera que el ex-director Eliseo Gil tiene algo que ver con una falsificación de inscripciones o informes, pero sorprendentemente estamos en camino al juicio oral, aunque 6 meses después de la apertura del juicio oral todavía no existe fecha.

Yo personalmente, como geólogo especializado en geoquímico, estoy muy convencido de que de un número de piezas muy relevantes, muchas llamadas excepcionales, existen múltiples indicios de la antigüedad de sus inscripciones. No dejar investigar las piezas por laboratorios especializados en arqueometría es un crimen contra la objetividad, y la justicia.

Dejar un inocente 10 años con la pena del banquillo es un crimen contra la humanidad.

—————–

Performance en el Guggenheim para denunciar ‘la injusticia judicial de Iruña-Veleia’

https://www.eitb.eus/es/noticias/sociedad/detalle/5998599/caso-iruna-veleia-realizan-performance-denuncia-guggenheim-bilbao/

UNA MUY LÚCIDA CARTA DE GONTZAL FONTANEDA PUBLICADA EN GARA-NAIZ:

La Diputación Foral de Álava en 2008, sin haber llevado los grafitos a analizar, por lo tanto sin saber si son auténticos o falsos, expulsó del yacimiento a Eliseo Gil y a su equipo arqueológico acusándolos de falsificación.

Acto seguido en 2009 presentó una denuncia en el juzgado, una trampa brillante: una vez el asunto en los tribunales, ya no hay prisa, pasarán años (de momento el juzgado lleva 9 años y medio buscando una prueba) y pronto el tema se olvidará (en esto se equivocaron).

Entregó la dirección del yacimiento a la Universidad del País Vasco, y ambas difundieron en prensa, radio y televisión sus especulaciones hasta convencer a buena parte de la ciudadanía, profana en estos temas, de que los grafitos eran falsos.

Sin embargo, todo lo que tienen son unos informes de la Universidad y de la policía, que proclaman la falsedad pero que no aportan prueba alguna, solo teorías, conjeturas y opiniones. Por el contrario, hay muchos informes que defienden que no hay razón para que los grafitos no sean auténticos [ver toda la historia con los documentos que la atestiguan: www.veleia.fontaneda.net].

Los poderes político y académico rehuyen la solución, que es bien sencilla: analizar los grafitos para saber en qué época fueron grabados y hacer excavaciones controladas para ver si aparecen más grafitos; y se acabó el problema. Si fueran falsos, ya tendrían la prueba, pero si fuesen auténticos, serían un tesoro de la humanidad que lleva 10 años escondido. Es incomprensible que sea el propio acusado Eliseo Gil quien pida al juzgado la solución y que la parte acusadora se niegue.

Aquella trampa de llevar el caso al juzgado además sirve de disculpa para no mover un dedo al Gobierno Vasco, a la Diputación Foral de Álava, a las Juntas Generales de Álava, a la Academia de la Lengua Vasca, a la Universidad del País Vasco y a los partidos políticos vascos, instituciones todas tan defensoras de Álava, del País Vasco, del euskera, de la cultura y de la historia que, cuando se les pide su colaboración, miran para otro lado: «el caso está pendiente de juicio», «hay que esperar a que la justicia resuelva», «hay que respetar las competencias»; si todo lo que tendrían que hacer es presentar una solicitud en el juzgado…

Aunque proclaman que «lo primero son las personas», no les preocupa que lleven 10 años en juego el honor, el prestigio profesional y la economía de Eliseo Gil, quien, sin prueba alguna y mientras no demuestren lo contrario, es inocente.

Por todo ello, tengas la opinión que tengas, si deseas mirar el problema de frente y colaborar con la justa reivindicación de que se analicen los grafitos, se te invita a firmar el “Manifiesto en favor del esclarecimiento del caso Iruña-Veleia”: iruñaveleia.eu en internet.

Con el mismo fin, se te invita también a la concentración que se celebra en Vitoria todos los jueves a las 8 de la tarde delante del palacio de la Diputación.

¿Están las raíces del euskera en Tierras Altas?

El arqueólogo Eduardo Alfaro descubre en su trabajo, que pronto será publicado por Soria Edita, una conexión de esta zona de la provincia con la población vascona incluso anterior a la romanización

http://www.heraldodiariodesoria.es/noticias/cultura/estan-raices-euskera-tierras-altas_119982.html

|

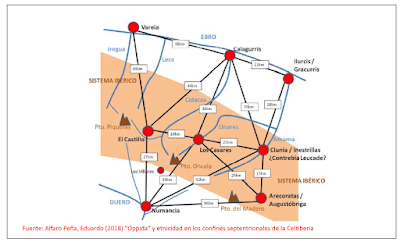

| Situación de la zona de estudio Fuente: Alfaro Peña, Eduardo (2018) |

La tesis doctoral de Eduardo Alfaro, titulado «»Oppida» y etnicidad en los confines septentrionales de la Celtiberia» que descubrimos a continuación, trata tanto arqueología urbana, fuentes clásicas y epigrafía, y nos enseña una complejidad cultural.

Su investigación le lleva a la conclusión de que la margen derecha del Ebro (La Rioja hasta el norte de Soria) era ocupado por entre otros tribus vascohablantes (alguna forma de euskera antiguo) en intima relación con el mundo celtíbero e íbero, y la conclusión de que la presencia de proto-euskera puede ser anterior a los celtas:

ÁREA ANTROPONÍMICA VASCONA

Desde que U. Espinosa afirmase hace ya un cuarto de siglo que la matriz onomástica de los nombres indígenas de las actuales Tierras Altas sorianas no es céltica sino que estaba relacionada con el mundo ibérico del valle del Ebro, la sucesiva localización de nuevas inscripciones funerarias ha incidido en su distanciamiento lingüístico respecto de sus vecinas laderas meridionales de la Cordillera Ibérica soriana, el tradicional territorio arévaco-pelendón de Numancia y los castros del alto Duero. A Lesuridantar, Oandissen, Arancis y Agirsenus (Espinosa 1992: 908-910; Beltrán 1993: 266-269) se han ido añadiendo nuevos nombres como Sesenco, Velar—Thar (o Ar—thar, según qué autores), Onso/Onse,etc., que trabajos sucesivos han vinculado cada vez con más firmeza al valle del Ebro, incidiendo en su más clara relación con un vasco antiguo, protovasco o vasco-aquitano.

Esta onomástica indígena de los altos cursos del Cidacos y el Linares sorianos ha fortalecido la hipótesis de que antes de que se impusiese una lengua céltica y después latina en la ribera riojano-navarra se habló una lengua euskérica al sur del Ebro, especialmente en el territorio comprendido entre Calagurris y Cascantum, lengua que se proyectaría por el sur hasta nuestros valles (Martínez Sáenz y González Perujo 1998: 186-491; Ramírez 2009: 142-143; Aznar 2011: 88, 92, 149). El análisis detallado de la onomástica indígena ha llevado a J. Gorrochategui (2009: 543-544) a la inclusión de los cursos altos de Cidacos y Linares en un área antroponímica vascona.

Queda meridianamente claro que la antroponimia indígena altoimperial del alto Cidacos y Linares no es céltica, y que sus vínculos lingüísticos originarios apuntan hacia el mundo ibérico y/o vascón del valle del Ebro inmediato. Muy probablemente estas gentes llevaban siglos asentadas y adaptadas a las nada fáciles condiciones físicas y climáticas de la profundidad serrana, altos valles de montaña donde habían desarrollado una particular economía mixta en la que, sin renunciar a las expectativas generadas por el desarrollo de la agricultura cerealista durante el Segundo Hierro, mantenían como principal base de su riqueza a una amplia cabaña ganadera en sintonía con las óptimas condiciones de sus montañas como estivaderos. Otro elemento también onomástico que incide en separar a este grupo humano del mundo indoeuropeo es la ausencia de mención alguna a organizaciones suprafamiliares, las gentilitates, en el medio centenar de nombres atestiguados.

p. 443-444

También muy interesante son sus conclusiones relacionadas con las menciones del termino ‘vascón’ por los autores clásicas como un invento administrativo romano:

LA MARGEN DERECHA DEL EBRO: UN TERRITORIO ÉTNICA Y LINGÜÍSTICAMENTE COMPLEJO

Los datos étnicos de los ríos de la margen derecha del Ebro riojano-navarra durante el periodo de conquista se presentan muy complejos, por una parte hay cierta indefinición en las fuentes, independientemente de que en ellas se atisbe el predominio del componente celtibérico en lo político y también en la cultura material, a lo que se suma por otra parte la inseguridad político-territorial, motivada por las décadas de conflictos que generaron cambios y fluctuaciones fronterizas con la desaparición de poblaciones por destrucción y/o abandono, y la más que probable situación transitoria de algunos espacios como tierras de nadie.

Como se ha apuntado, este predominio o al menos presencia celtibérica debió de compartirse con otros pueblos, ciudades y lenguas ibéricos y protovascos. Se trata por tanto de un territorio y unos siglos en los que convergen y conviven lenguas y pueblos de diferente raíz ―indoeuropea, vasca e ibérica― sobre los que se superpone el latín (Beltrán 1993: 235-236; Burillo 1998: 178-182; Pina 2009: 208-209).

Por lo que al territorio de estudio se refiere, hay que preguntarse hasta qué punto no fue el s. II a.C., el siglo de los oppida, el momento en que se consolidó una celtiberización cultural de estos valles que ya estaba avanzada. La potencia invasora estaba cada vez más afianzada y su influencia crecía en el sector bajo del Cidacos y el Alhama, mientras que en sus sectores altos, nuestros oppida serranos con su territorio agreste y de complicada orografía, se mantenían como una de las primeras líneas de contacto o contención en comunión de intereses con sus vecinos meridionales, el “núcleo duro” celtibérico del momento representado por arévacos y pelendones (Roldan y Wulff 2001: 595). Desde el punto de vista tipológico es con la Numancia arévaca con la que más convergencias presentan los materiales analizados de El Castillo y Los Casares. Como bien se ha apuntado, esta más que probable cooperación entre pueblos indígenas ante el avance y la presión externa provocó que poblaciones que, con propiedad, no eran desde el punto de vista étnico celtibéricas se integrasen mediante alianzas en coaliciones genéricamente definidas como tales, especialmente por Roma, que parece que acuñó el término celtibérico precisamente para definir a las gentes con las que se enfrentan en el proceso de conquista de la Meseta oriental (Sánchez Moreno, Pérez Rubio y García Riaza 2015: 77).

Los vascones no aparecen en las fuentes hasta las Guerras Sertorianas del primer tercio del siglo I a.C. (Livio, Per. 91), circunstancia en la que está incidiendo la historiografía más reciente. Cada vez son más los investigadores que apuestan por que los vascones, tal y como se presentan en Ptolomeo (II, 6, 67) en el siglo II d.C., son una etnia creada por Roma con fines administrativos, línea de investigación que renuncia a la tradicional visión de una supuesta expansión vascona por la margen derecha del Ebro tras las guerras de conquista y a costa de los pueblos celtibéricos (Bosch 1933b: 8 bis; Burillo 1998: 170-171, 330-333).

Roma habría dado forma en torno a este etnónimo a un territorio que iba desde el Pirineo occidental hasta el Sistema Ibérico, y que étnica y lingüísticamente aglutinaba a un conjunto de pueblos y ciudades de habla ibérica, indoeuropea y propiamente vascona entre los que dominaba probablemente el componente celtibérico o el ibérico. Las comunidades locales de habla vascona no tendrían la consciencia étnica que les otorgaba la historiografía tradicional, se trataría de una concienciación adquirida a posteriori, en un momento indeterminado a partir de la creación administrativa romana. En definitiva, en torno a lo que se denominan vascones Roma habría aglutinado a la variopinta y compleja población que habitaba el valle del Ebro al sur del Pirineo occidental y al norte del Sistema Ibérico (Sayas 1998: 89-139; Roldán y Wulff 2001: 408-410; Wulff 2009: 47; Beltrán y Velaza 2009:105-108; Pina 2009: 214; Navarro 2009: 292).

Los datos culturales y sobre todo étnicos de Tierras Altas de Soria en los siglos inmediatos al cambio de Era presentan por tanto una importante ambigüedad. La lectura que entendemos es la más adecuada para el caso es la que ve en la etnicidad un proceso dinámico en el que se van superponiendo realidades e influencias culturales, aunque con áreas más permeables que otras. La profundidad de la serranía sería más propensa a cierta reclusión de sus gentes y por tanto a la supervivencia de determinadas muestras de situaciones pretéritas.

M. L. Albertos ya apuntó la pervivencia en el interior serrano de pequeños grupos humanos con antroponimia no céltica, burbujas culturales o identidades diferenciadas que estarían reflejado realidades de unos tiempos más remotos, a la par que sitúa a las actuales Tierras Altas de Soria como un territorio de frontera lingüística (Albertos 1966: 274-275; Espinosa 1992: 908; Hoz 2005: 58; Gorrochategui 2009: 546).p. 444-445

La parte que quizás más nos interesa es su interpretación de la onomástica indígena:

Algunos productos epigráficos de talleres de las Tierras Altas

Fuente: Alfaro Peña, Eduardo (2018)2. Los cognomina indígenas

Ha podido apreciarse cómo los cognomina latinos encajan sin dificultad en el puzzle onomástico que rodeaba a las actuales Tierras Altas de Soria en época altoimperial, la línea de ciudades vinculadas a las vías del Ebro y del Duero, cerrada a poniente por la proyección de la Serranía Ibérica hacia Urbión y la Demanda. No puede decirse lo mismo de sus nombres indígenas pues parecen pertenecer a otro rompecabezas.El femenino Onse y su masculino Onso es el más repetido y, como la mayoría de los indígenas, totalmente autóctono, exclusivo de estos valles, presente en estelas de Yanguas, Navabellida y El Collado.

Una variante de Onse parece ser el cognomen de la adolescente Antestia Oandissen (Valloria). Si pensamos en su forma con la desinencia latinizada, Oandissen-a, y la comparamos con la de un individuo de Vizmanos, Agirsen-us, puede apreciarse y aislarse mejor un mismo radical indígena, SEN, también presente en un joven de La Laguna, Antestius Se-sen-co. Serían por tanto nombres compuestos en los que el radical ―SEN aparece como segundo componente. Julio Caro Baroja (1946: 150-154) y Mª L. Albertos (1966: 209-211, 260-273) fueron pioneros en proporcionar algunas claves para orientar sobre el substrato al que remiten estos nombres. Como ibérico se aísla el radical sen― (Sen-ario), que también aparece en el vasco (Sen-ar, Sen-ide) y aquitano (Sen-ar, Sen-arri).

También ibérico es el radical Agir― (Agir-nes, Arsgi-tar, Acir-senio). Formas próximas a Oandis― se encuentran en el vasco (Aundi―, ‘grande’) y en el aquitano (And-osso). Son todas formas ajenas al mundo indoeuropeo y céltico que se presupone a los pueblos asociados al territorio circundante, berones, pelendones y arévacos; conociendo esta onomástica resulta muy complicado asignar dicho substrato étnico a estos valles montaraces del norte soriano. Incide en los lazos con el territorio pirenaico e ibérico la fonética de nombres como Soson-nis (aquitano), Soson-tigi, Sosin-buru, Sosin-aden Sosin-asae (ibéricos pirenaicos), Sisen, Sisena, Siseanba… (béticos), de indudable cercanía a los serranos Sesenco, Oandissen, Onse y Onso. Recientemente se han encontrado equivalencias en términos vascos (Gorrochategui 1987: 440; 2007: 633-634; Gimeno 1989: 235; Velaza 1995: 213; Aznar 2011: 154-159, 174,178, 182-189, 200-202).

Desde un punto de vista lingüístico Caro Baroja excluyó hace ya 60 años al serrano Lesuridantar (Munilla) del celtismo pelendón y castreño en el que se integraba arqueológicamente toda la serranía soriana. Incluyó el nombre en el hispánico antiguo, como Arsgi-tar, encontrando también paralelos en el vasco, como baserri-tar ‘habitante del monte’[¿?] (Caro 1946: 150-154). Años más tarde MªL. Albertos incluyó sin dudas Lesuridantar entre los nombres ibéricos (Albertos 1966: 130). La localización hace un par de décadas de una estela en El Collado con el cognomen Velar[–]-thar incide en el vínculo onomástico serrano con el Pirineo vasco-aquitano y el mundo ibérico del Ebro, por un lado con la desinencia ―tar, como se ha visto frecuente en su antroponimia y también como elemento para conformar genitivos, por otro con el radical Vel― conocido en nombres ibéricos como Vel-aunis, Vel-gana, etc. (Albertos 1966: 245, 260-273; Gorrochategui 2007: 633; Aznar 2011: 160-161, 193-194, 204-211).

La desinencia ―tar se declina en la sierra como nombre de la tercera, temas en consonante o -i, inercia que siguen buena parte de sus nombres indígenas, palpable en los genitivos Lesuridantaris, Arancisis, Attasis y en el dativo Nopri; todos son de varones, masculinos. Los nominativos Onse, Onso, Oandissen, Haurce, Sesenco y Bugan no presentan las habituales desinencias latinizadas, en ̶a/–us, no está clara por tanto su declinación. Únicamente el genitivo Agirseni es sin duda de la segunda. Parece por tanto que la onomástica indígena tiene dificultades para latinizar sus desinencias con los habituales temas en ―a (femenino) y sobre todo on el masculino tema en ―o pues se recurre habitualmente a la tercera para su declinación (Albertos 1966: 282; Reyes 2000: 110).

Sí se declinan por la segunda los indígenas Balanus y Murranus, tal vez porque su origen apunta en otra dirección. Livio menciona a un rey de la Galia Trasalpina llamado Balanos, y el nombre aparece también en una inscripción de Trujillo (Cáceres) (Palomar 1975: 47). En opinión de Mª L. Albertos (1966: 162-163) Murranus derivaría de la forma indoeuropea murro, que se ha traducido como ‘hocico’ y ‘punta de roca’. Habría llegado al español en la forma ‘morro’, ‘labios gruesos’. Es un nombre atestiguado en la Hispania céltica (Clunia) pero también en Levante, fuera de la Península se conoce en Galia, Britania, Germania,…

En el nombre Attasis también puede verse una variante del céltico atta, ‘padre’, bien conocido y repetido en poblaciones próximas, especialmente en el entorno de Augustobriga (Muro de Ágreda y Trébago). Sin embargo también existen paralelos en el vasco aita, ‘padre’ y en nombres compuestos definidos por Caro Baroja como de un hispánico antiguo (Ata-bels). En cualquier caso el antropónimo Atta y sus derivados son frecuentes en gentes indoeuropeas extrapeninsulares como visigodos, hunos, Gálatas, ilirios, etc. (Aznar 2011: 162-167).

Resumiendo, los nombres indígenas serranos están emparentados, sin duda, con el mundo del Ebro y el Pirineo, desde Cataluña hasta el País Vasco,incluso Aquitania lo que apunta a una ancestral tradición onomástica previa o paralela al celtismo peninsular (Espinosa 1992: 907; Beltrán 1993: 266-269), también representado en nombres como Balanus y Murranus. Esta interrelación y convivencia entre elementos evocadores de un mundo ibérico y el pirenaico con otros, casi testimoniales, indoeuropeos se justifica por la vecindad, y también por la fuerte presión de los grupos humanos, incluso por los movimientos de gentes que pudieron generar grupos sueltos residuales. La más reciente investigación lingüística al respecto incide con fuerza en la relación de la onomástica serrana con una lengua ibérica o vascoaquitana del inmediato valle del Ebro (Martínez Sáenz y González Perujo 1998: 490-495; Gorrochategui 2007: 634; 2009: 543-544; Aznar 2011: 143-152, 257-258). p. 414-416

Lo que llama la atención es que el arqueólogo en su doctorado de alguna manera intenta enmascarar sus conclusiones sobre vascohablantes en las Tierras Altas, lo que ya hemos observado en sus otras publicaciones. Lo vamos observando en su resumen donde no se precisa quien son los vecinos de los celtiberos del norte de Soria:

Se estructura el trabajo en dos apartados. Por un lado un estudio de poblamiento que afecta a las vertientes septentrionales del Sistema Ibérico soriano oriental (valles del Cidacos, Linares y Alhama) desde época celtibérica avanzada hasta los tiempos del Alto Imperio Romano, y por otro un estudio epigráfico en el que se analiza el nutrido grupo de inscripciones altoimperiales localizadas en estos valles. El estudio de poblamiento se centra principalmente en el análisis de los dos oppida del territorio, cabezas jerárquicas de sendas ciudades estado que capitalizan la vida política en este sector de la serranía, y que se abordan desde dos tipos de intervención arqueológica diferenciados, El Castillo de La Laguna desde la prospección y Los Casares de San Pedro Manrique desde los datos que aporta la excavación arqueológica en un sector inmediato a su muralla. El objetivo, conocer las características del poblamiento, el urbanismo y la cultura material de ambos oppida y sus territorios, lo que va a permitir establecer comparaciones con ciudades y espacios vecinos del entorno serrano inmediato, del valle del Ebro y de la Meseta.

Es penoso que en un país moderno se tiene que medir tanto sus palabras cuando se habla del euskera como patrimonio de todos. Ver también las noticias de La Rioja: La referencia al euskera en el Estatuto por parte del PSOE desata una ola de protestas.

Mucho de lo afirmado en este tesis encontramos con menos envoltorios en Gorrochategui (2018) en HISTORIA DE LA LENGUA VASCA:

«El conjunto onomástico de las Tierras Altas de Soria posee, aun en su pequeñez, muchas caracteristicas de la onomástica aquitana: correlatos nitidos como zezen, las bases seni, atta, y on, los sufijos -co, -so, -se y -thar, distribución complementaria entre los sufijos -co, -so, -se y -thar, distribución complementario entre los suf. -so y -se según el sexo del referente y presencia de aspiración. Es difícil pensar que la reunión de todos estos rasgos a la vez en un conjunto reducido de nombres sea debido a la casualidad.

Según lo anterior, aunque tengamos por seguro que una parte al menos de esta sociedad era hablante del vasco antiguo, no es tan fácil dar cuenta de la presencia de estos hablantes en la zona. Puede ser que la lengua vasca fuera en esas tierras lengua autóctona anterior a la extensión y difusión del celtibérico hacia el valle del Ebro, en sintonía con lo que pensaba sobre la Rioja, Merino Urrutia hace años (…)»

| Título: | «Oppida» y etnicidad en los confines septentrionales de la Celtiberia | |

| Autor: | Alfaro Peña, Eduardo | |

| Editor: | Universidad de Valladolid. Facultad de Filosofía y Letras | |

| Director o Tutor: | Romero Carnicero, Fernando, dir. | |

| Año del Documento: | 2018 |

Descargar aquí