AbstractThe cross, seen and exalted in a great many biblical or natural types and figures, entered the sacramental, cultic, and private lives of Christians already in the sub-apostolic period as a seal of God, a sign of Divine Presence, as salvation and protection. The early Christians prayed before the cross as a seal of God in the sacraments and a sign of eschatological salvation, possibly turned towards the east. They also placed the cross in their homes, in cultic places, and in cemeteries. Contrary to what is commonly held, the origin of the cross and its adoration are pre-Constantinian.

Both are attested in the works of Minucius Felix and Tertullian, and confirmed by numerous testimonies from monuments. With Constantine, the honour and veneration of the cross became more noted and public. However the turning point of the cross from a sign of ignominy to a sign of glory cannot be attributed to the vision of the emperor. The cross was used by Christians already in the first years of the life of the Church, and the veneration of the cross goes back at least to the end of the 2nd century. It is an important confirmation that the cross was not an instrument of torture, but was venerated for its unique link with the life, mission and work of the Redeemer of humanity.

Queda la gran pregunta: ¿y por qué no encontramos más cruces?

LIBER XII.1. Sed et qui crucis nos antistites affirmat, consa cerdos erit noster. Crucis qualitas signum est de ligno: etiam de materia colitis penes vos cum effigie.2. Quamquam sicut vestrum humana figura est, ita et nostrum. sua propria. Viderint nunc liniamenta, dum una sit qualitas; viderit forma, dum ipsum sit dei corpus.3. Quodsi de hoc differentia intercedit, quanto distinguitur a crucis stipite Pallas Attica et Ceres Pharia, quae sine forma rudi palo et solo staticulo ligni informis repraesentatur? Pars crucis, et quidem maior, est omne robur quod derecta statione defigitur.4. Sed nobis tota crux imputatur, cum antemna scilicet sua et cum illo sedilis excessu. Hoc quidem vos incusabiliores, qui mutilum et truncum dicastis lignum, quod alii plenum et structum consecraverunt!5. Enimvero de reliquo integra est religio vobis integrae crucis, sicut ostendam. Ignoratis autem etiam originem ipsam deis vestris de isto patibulo provenisse.6. Nam omne simulacrum, seu ligno seu lapide desculpitur, seu aere defunditur, seu quacumque alia locupletiore materia producitur, plasticae manus praecedant necesse est.7. Plasta autem lignum crucis in primo statuit, quoniam ipsi quoque corpori nostro tacita et secreta linea crucis situs est, quod caput emicat, quod spina dirigitur, quod umerorum obliquatio ; < . . . . . . >; si statueris hominem manibus expansis, imaginem crucisfeceris.8. Huic igitur exordio et velut statumini argilla desuper intexta paulatim membra complet, et corpus struit, et habitum, quem placuit argillae, intus cruci ingerit;9. inde circino et plumbeis modulis praeparatio simulacri, in marmor, in lutum vel aes vel argentum, vel quodcumque placuit deum fieri, transmigratura. A cruce argilla, ab argilla deus: quodammodo transit crux in deum per argillam.10. Crucem igitur consecratis, a qua incipitur consecratus. Exempli gratia dictum erit: nempe de olivae nucleo et nuce persici et grano piperis sub terra temperato arbor exsurgit in ramos, in comam, in speciem sui generis.11. Eam si transferas, vel de brachiis eius in aliam subolem utaris, cui deputabitur, quod de traduce provenit? Non illi grano aut nuci aut nucleo? Nam cum tertius gradus secundo adscribitur, aeque primo secundus, sic tertius redigetur ad primum transmissus per secundum.12. Nec diutius super isto argumentandum est, quando naturali praescriptione omne omnino genus censum ad originem refert, quantoque genus censetur origine, tanto origo convenitur in genere.13. Si igitur in genere deorum crucem originem colitis, hic erit nucleus et granum primordiale, ex quibus apud vos simulacrorum silvae propagantur.14. Ad manifesta iam. Victorias ut numina, et quidem augustiora, quanto laetiora, veneramini. Consecratio ne quid melius extollat, cruces erunt intestina quodammodo et tropaeorum; itaque in Victoriis et cruces colit castrensis religio.15. Signa adorat, signa deierat, signa ipsi Iovi praefert: sed ille imaginum suggestus et totus auri cultus monilia crucum sunt.16. Sic etiam in cantabris atque vexillis, quae non minore sanctitate militia custodit, siphara illa vestes crucum sunt. Erubescitis, opinor, incultas et nudas cruces colere!Book XII

As for him who affirms that we are «the priesthood of a cross, we shall claim him as our co-religionist. A cross is, in its material, a sign of wood; amongst yourselves also the object of worship is a wooden figure. Only, whilst with you the figure is a human one, with us the wood is its own figure. Never mind for the present what is the shape, provided the material is the same: the form, too, is of no importance, if so be it be the actual body of a god. If, however, there arises a question of difference on this point what, (let me ask,) is the difference between the Athenian Pallas, or the Pharian Ceres, and wood formed into a cross, when each is represented by a rough stock, without form, and by the merest rudiment of a statue of unformed wood? Every piece of timber which is fixed in the ground in an erect position is a part of a cross, and indeed the greater portion of its mass. But an entire cross is attributed to us, with its transverse beam, of course, and its projecting seat.

Now you have the less to excuse you, for you dedicate to religion only a mutilated imperfect piece of wood, while others consecrate to the sacred purpose a complete structure. The truth, however, after all is, that your religion is all cross, as I shall show. You are indeed unaware that your gods in their origin have proceeded from this hated cross.

Now, every image, whether carved out of wood or stone, or molten in metal, or produced out of any other richer material, must needs have had plastic hands engaged in its formation. Well, then, this modeller, before he did anything else, hit upon the form of a wooden cross, because even our own body assumes as its natural position the latent and concealed outline of a cross. Since the head rises upwards, and the back takes a straight direction, and the shoulders project laterally, if you simply place a man with his arms and hands outstretched, you will make the general outline of a cross. Starting, then, from this rudimental form and prop, as it were, he applies a covering of clay, and so gradually completes the limbs, and forms the body, and covers the cross within with the shape which he meant to impress upon the clay; then from this design, with the help of compasses and leaden moulds, he has got all ready for his image which is to be brought out into marble, or clay, or whatever the material be of which he has determined to make his god. (This, then, is the process:) after the cross-shaped frame, the clay; after the clay, the god. In a well-understood routine, the cross passes into a god through the clayey medium. The cross then you consecrate, and from it the consecrated (deity) begins to derive his origin.

By way of example, let us take the case of a tree which grows up into a system of branches and foliage, and is a reproduction of its own kind, whether it springs from the kernel of an olive, or the stone of a peach, or a grain of pepper which has been duly tempered under ground. Now, if you transplant it, or take a cutting off its branches for another plant, to what will you attribute what is produced by the propagation? Will it not be to the grain, or the stone, or the kernel? Because, as the third stage is attributable to the second, and the second in like manner to the first, so the third will have to be referred to the first, through the second as the mean.

We need not stay any longer in the discussion of this point, since by a natural law every kind of produce throughout nature refers back its growth to its original source; and just as the product is comprised in its primal cause, so does that cause agree in character with the thing produced. Since, then, in the production of your gods, you worship the cross which originates them, here will be the original kernel and grain, from which are propagated the wooden materials of your idolatrous images. Examples are not far to seek. Your victories you celebrate with religious ceremony as deities; and they are the more august in proportion to the joy they bring you.

The frames on which you hang up your trophies must be crosses: these are, as it were, the very core of your pageants. Thus, in your victories, the religion of your camp makes even crosses objects of worship; your standards it adores, your standards are the sanction of its oaths; your standards it prefers before Jupiter himself, But all that parade of images, and that display of pure gold, are (as so many) necklaces of the crosses. in like manner also, in the banners and ensigns, which your soldiers guard with no less sacred care, you have the streamers (and) vestments of your crosses. You are ashamed, I suppose, to worship unadorned and simple crosses.(http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/tertullian06.html)

Quinto Septimio Florente Tertuliano, más comúnmente conocido como Tertuliano (ca. 160 – ca. 220)1 fue un padre de la Iglesia y un prolífico escritor durante la segunda parte del siglo II y primera parte del siglo III. .. Nació, vivió y murió en Cartago y ejerció una gran influencia en la Cristiandad occidental de la época. (De Wikipedia)

La evidencias del staurograma tau-rho como ‘cruz vestida’:

Larry Hurtado. The staurogram in early christian manuscripts: the earliest visual reference to the crucified Jesus?

In New Testament Manuscripts: Their Text and Their World, ed. Thomas J. Kraus and Tobias Nicklas. “Texts and Editions for New Testament Study,” 2. Leiden: Brill 2006. Pp. 207-26.

|

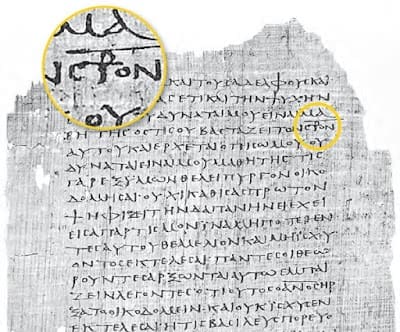

| Un staurograma utilizado el papiro P75 en el siglo segundo Papyrus Bodmer XIV-XV para representar la palabra cruz en (Lucas 14:27) (Wikipedia) |

1) The “Staurogram” (the combination of the Greek letters tau and rho) did not derive from the chi-rho. We have instances of the Christian use of the tau-rho considerably earlier than any instances of the chi-rho. These earliest uses of the tau-rho are in Christian manuscripts palaeographically dated ca. 200-250 CE.

2) Unlike the chi-rho, which is used purely as a free-standing symbol, the earliest uses of the tau-rho are not as such free-standing symbols, but form part of a special way of writing the Greek words for “cross” (stauros) and “crucify” (stauro-o), in NT texts which refer to the crucifixion of Jesus.

3) The tau-rho is not an allusion to the word “christos“. Indeed, the letters have no relation to any terms in early Christian vocabulary. Instead, the device (adapted from pre-Christian usage) seems to have served originally as a kind of pictographic representation of the crucified Jesus, the loop of the rho superimposed on the tau serving to depict the head of a figure on a cross.

4) So, contra the common assumption taught in art history courses, the earliest visual reference to the crucified Jesus isn’t 5th century intaglia, but this scribal device employed by ca. 200 CE. This amounts to a major shift.

Sobre la datación del grafito de Alexameno [grafito blasfemico del Palatino; grafito del asno crucificado]

El único artículo relevante y completo que he encontrado es:

Thomas R. Young.The Alexamenos Graffito and Its Rhetorical Contribution to Anti-Christian Polemic (2015)

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2546438

Concluye que a base de la información arquitectonica (parte del palacio de Caligula, reformado en diferentes momentos) y los argumentos de los escritos de Tertullianus en Apología, la datación debe situarse entre el final del siglo segundo y como más tarde la segunda decada del siglo tercero.

III. Dating the Alexemnos Graffitto

Dating the Graffito, even given the significant accretion that has occurred in the domus Gelotiana, is not beyond the realm of possibility given the many clues which are available, both within the structure and through available texts. The conclusion reached by scholars Ferdinand Becker and John Hogg is that the graffiti dates to the late second to early third century, perhaps created during the reign of Septimius Severus.57 The justification given by Becker for such dating relates largely to Tertullian’s reference in his Apology to similar tales of the Christians worshipping an ass-headed god.58 The argument simply stated is that Tertullian writing of the Apology, which references stories of Christian worship of an ass-headed god, approximates to the year 197, which in turn coincides with the reign of Septimius Severus.59 John Hogg, for his part, relates that the wall on which the graffiti was found was not only a part of Caligula’s Domus Gelotiana but also part of the Septizonium, a complex built by Septimius Severus (193-211 C.E.)on the same site on the Pallatine Hill, which if correct would confirm a date of the third century.60 As mentioned before, Peter Keegan, when surveying the literature, found evidence of architectural elements which spanned the reins of the Emperor Caligula to that of Septimius Severus.

Taking the evidence provided by Tertullian along with the architectural evidence, it seems highly probable that the dating of the Alexamenos Graffito could not be any earlier than the late second century or any later than second decade of the third century.