En este post quiero aportar una investigación bibliográfica sobre cruces y calvarios (nada es casualidad).

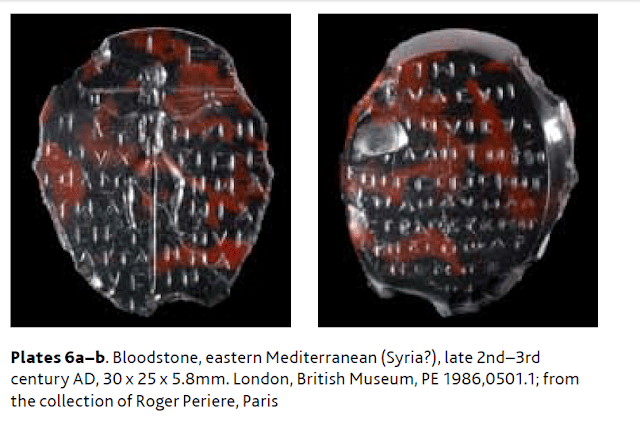

El punto de salida ha sido un post de hace dos años de Alicia Satué (Q.V.R.I.P., o cuándo descansará en paz Veleia), donde se nos da un resumen de las evidencias de Veleia, y se nos aporta lo que es después de fisgonear en internet un amuleto o talismán con formulas mágicas y la inscripción en griego EMMANUEL (dios es con nosotros, una formula con que se designa normalmente Jesús), acompañado del texto HIJO, PADRE, JESÚS CRISTOS y palabras mágicas (Felicity Harley 2007).

Este tesoro parecía hasta entonces desconocido en el asunto de Veleia. Ella lo trajo a su vez del informe de Héctor Iglesias (pág. 162) donde leemos (argumentando contra Isabel Velazquez):

« Aunque, como se ha advertido, en este informe no se consideran aspectos iconográficos, sí hay que hacer referencia por un lado a la presencia de representaciones de calvarios, por cuanto que alguno lleva la inscripción “R.I.P.” » [cita de Veazquez]

.

Elle ajoute :

« La representación de las tres cruces es posterior en el tiempo, en especial con reproducción de una figura crucificada ».

Inexact.

Voici quelle était jusqu’à présent la plus ancienne représentation du Crucifié connue avant la découverte des inscriptions « veleyenses ».

Et cette représentation, dont voici une photographie 13, date du IIIe siècle.

¿Qué es esta misteriosa pieza de un hombre crucificado con un fondo de letras griegas que nadie había mencionado hasta entonces?

Se encuentra en el British Museum, y en su ficha de catálogo encontramos:

magical gem – intaglioMuseum number : 1986,0501.1Description: Magical gem; intaglio; green-brown jasper; oval; bevelled edge on side B.Side A: Crucified figure on a tall cross with a short base. The wrists are tied to the cross, feet held as if hanging in the air, bearded head with long hair in profile to left. Letters in the free field, above the head of the figure. Inscription in eight lines to the left and right of the image.Date: 2ndC-3rdCProduction place: Mediterranean (eastern Mediterranean)Materials: jasper (green-brown)Technique: engravedDimensionsHeight: 30 millimetresWidth: 25 millimetresThickness: 6 millimetresSide A: · Inscription Language: Greek

· Inscription ContentΠΑΤΗΡΙΗ / CΟΥΧΡΙCΤΕ / CΟΑΜΝWΑ / ΜWΑWΙΑ / .CΗΙΟΥW / .ΑΡΤΑΝΝΑ /..ΥCΙΟΥ / ..Ι…· Inscription Translationπατήρ Ἰησοῦ Χριστέ

Father, Jesus Christ…Side B:· Inscription LanguageGreek· Inscription ContentΙWΕ / ΕΥΑΕΥΙΙ / .ΙΟΥΙCΥΕ / .ΑΔΗΤΟΦΝ / ΘΙΕCCΕΤCΚΗΕ / .ΜΑΝΑΥΗΛΑ / CΤΡΑΠΣCΤΚΜΗ / ΦΜΕΙΘWΑΡ / ΜΕΜΠΕ / ….· Inscription TranslationVariations of the names «Ἰησούς» (Jesus) and » Εμμανουήλ» (Emmanuel)

En el catálogo de la exposición (2007 18 Nov-2008 30 Mar, USA, Fort Worth, Kimbell Art Museum, Picturing the Bible: The Earliest Christian Art), y parece la única vez que ha sido mostrado al público, Felicity Harley (especialista mundial en arte paleocristiana y jaspes grabados) nos informa que es la representación del cristo crucificado más antigua del mundo:

The earliest surviving image of the crucified Christ is found in an entirely unexpected place, on an engraved magical gemstone of the late second or early third century (cat. 55). Whether of Christian or pagan origin, this amulet, like the graffito from Rome, no doubt drew on a preexistent pictorial source.

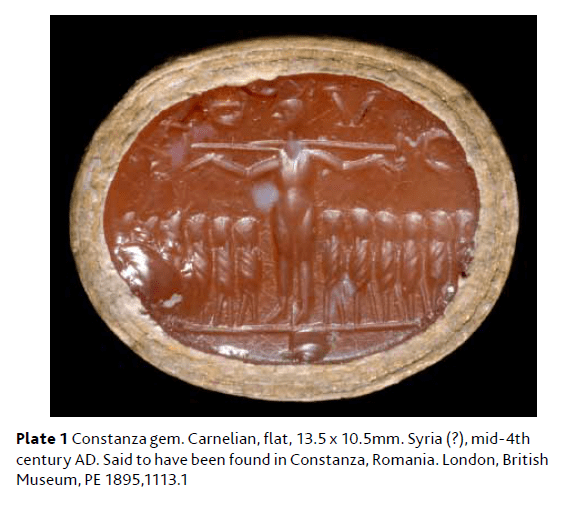

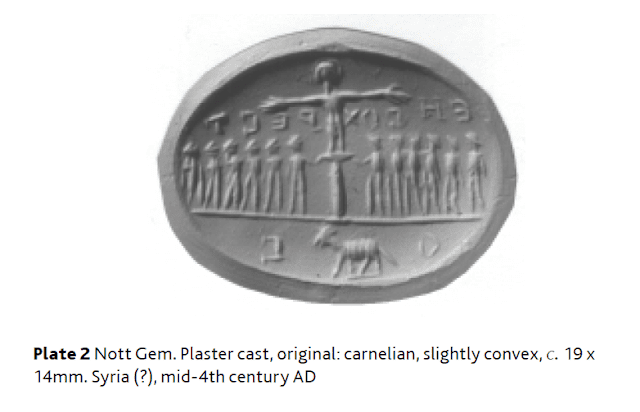

Two other engraved gems from the early fourth century considerably earlier in date than the Santa Sabina doors and the Maskell ivories are unconventional in that they depict Christ crucified in the presence of the twelve apostles (cat. 56), a composition in conflict with the Gospel account and instead conveying a dogmatic message similar to that seen on some mid-fourth-century sarcophagi in Rome.

Felicity Harley, The Crucification,

In Essay and catalogue entries in Jeffrey Spier, Picturing the Bible: The Earliest Christian Art (Yale University Press, 2007), pp. 227-232

In https://www.academia.edu/1787622/The_Crucifixion

La autora explica la presencia de elementos mágicos mezclados con elementos indudablemente cristianos de la siguiente manera:

Although the Church strongly disapproved of magical amulets, which were pervasive in the Greco-Roman world, some Christians did continue to use them.3 The image of the crucified Christ may, however, have been employed by a pagan magician, who borrowed what he perceived as a symbol of great power. Even in Jesus’s lifetime, pagans and Jews were said to use his name for magical purposes (Mark 9:38 – 41; Luke 9:49 – 50; and especially Acts 19:13 – 17, for the seven sons of the Jewish priest Sceva). The Christian theologian Origen wrote, “The name of Jesus is so powerful against the demons that sometimes it is effective even when pronounced by bad men” (Contra celsum 1.6).The Crucifixion, Jesus’s triumph over death itself, was regarded as a powerful symbol, and at an early date the formulaic phrase, “Jesus Christ, who was crucified under Pontius Pilate,” was used to control demonic forces. Peter, for example, heals a cripple in Christ’s name and states (Acts 4:10): “Be it known to you all, and to all the people of Israel, that by the name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, whom you crucified, whom God raised from the dead, by him this man is standing before you well.”

En sus conclusiones afirma en realidad más o menos lo defendido por Idoia Filloy en su informe sobre iconografía también:

The appearance of the Crucifixion on a gem of such an early date suggests that pictures of the subject (now lost) may have been widespread even in the late second or early third century, most likely in conventional Christian contexts.

La aparición de la crucificación en un jaspe grabado sugiere que los imágenes del crucifijo (ahora perdidos) pueden haber sido generalizadas en el segundo y tercer siglo, muy probablemente en un contexto cristiano convencional.

En otro artículo posterior Harley parece relativarlo y da enfasis a la escasez de fuentes:

According to the surviving evidence, the earliest images of the Crucifixion have generally been thought to have been produced in the West in the 5th century ad, relatively late inthe broad development of Christian iconography. The first dates to ad 420–30 and appears in the pictorial narrative of the Passion that is arranged across the series of ivory panels known as the Maskell Passion ivories(Pl. 8).The second, slightly later, representation is found amongst the cycle of episodes from the Old and New Testament illustrated on the wooden doors of the church of Sta Sabina in Rome, carved in the ad 430s (Pl. 9).

The evidence yielded from the study of engraved gemstones, which furnish even earlier representations of the subject, suggests that experimentation with pictorial representations of Jesus affixed to the cross had begun by the3rd century ad. While the experimentation might not have been extensive, or the results popular (given the paucity of evidence), the fact of it is very clearly if unexpectedly attested by the magical Pereire gem in the first instance, and the Constanza and Nott gems in the second.”

(F. Harley. The Constanza Carnelian and the Development of Crucifixion Iconography in Late Antiquity. C. Entwistle and N. Adams, Gems of Heaven: Recent Research on Engraved Gemstones in Late Antiquity (British Museum Press, 2011), pp. 214-220.

Una reflexión mía. Como vemos que las evidencias más importantes del siglo V son en madera (puerta Santa Sabina) y marfil (caja de marfil Maskell), una explicación podría ser que simplemente no se han conservado.

Las más antiguas representaciones conocidas de un Cristo en la cruz (según Harley 2011):

|

| Grafito con parodia sobre los que adoran a su Díos crucificado SIII. (Ver también informe iconográfico de Idoya Filloy) |

The earliest example of a visual reference to the Crucifixion is the ostensibly blasphemous graffito of c.200 excavated on the Palatine hill in 1856. Depicting adonkey-man affixed to a cross and hailed by a bystander, the drawing istraditionally interpreted as parody of the Christian worship of a crucified deity.It has a literary counterpart in the image of Jesus erected in Carthage around AD197, described by Tertullian ( Ad Nationes 1.114.1), which confirms both that the early Christians were accused of worshipping an ass and that caricature images of Christianity and its tenets were being executed around the turn of the thirdcentury. While there might be a temptation to interpret these drawings asimitations of images erected and worshipped by Christians in the third century,as in the case of the Palatine graffito and its depiction of a man striking the standard gesture of acclamation, with arm raised towards the cross, Balch suggests that the caricaturist may have been responding to a ‘word picture’ of Christ crucified, as is found at Galatians 3:1, rather than an actual cult image.It is important to observe however, that although the Palatine graffito’s iconographic reference to the Christian belief in and worship of a crucified deityis crude, it is remarkably prescient, exhibiting many of the rudimentary visualelements we find emerging for explicit representations of Jesus on his cross inChristian art after the fifth century — a fact which begs speculation with regard to iconographic models.Essay in John Burke et al, Byzantine Narrative: Papers in Honour of Roger Scott (Melbourne, 2006), pp. 221-232, images pp. 536-538.)

|

| Amulleto con la primer representación cristiana de un crucifijo, siglo II-III |

|

| Jaspe de Constanza, mitad del siglo IV (Ver también informe iconográfico de Idoya Filloy) |

|

| Jaspe de Nott, mitad del siglo IV, (Ver también informe iconográfico de Idoya Filloy) |

|

| Caja de Marfil de la colección Maskell, 420-430 AD. (Ver también informe iconográfico de Idoya Filloy) |

|

| Puerta de la iglesia Santa Sabina en Roma, c. 430 AD |

PD. Los escritos de la experta Felicity Harley de la Universidad de Yale, en Estados Unidos, son un tesoro para saber más sobre el asunto de crucifijos y calvarios, y arte paleocristiano. Sus artículos están escritos en un idioma muy lucido y accessible. Aqui se puede descargar su tesis doctoral: Images Of The Crucifixion In Late Antiquity: The testimony Of Engraved Gems Felicity Harley (2001), [Aportado por Percha en Celtiberia hoy]

Curiosamente todas las piezas aportadas son de antes de la segunda mitad del siglo V, que menciona prof. Volpes como fecha más temprana para ‘cruces vestidas’. Misterio, misterio.

Espero que esta información pueda inspirar a otros y otras 😉